II. Motor Boat Pioneer

"And if we admire Mr Halliday for his pluck, what will we say of the motor, and of the boat, which he himself had designed? It is such a triumph for British work and brains that

our duty is not done until we have given credit where credit is due."

The Motor Boat, 1905

our duty is not done until we have given credit where credit is due."

The Motor Boat, 1905

In the first decade of the twentieth century Halliday

was at the vanguard of early motor boat development and for a short

period between 1903 and 1909 designed numerous motor

launches including several entrants for the Harmsworth Trophy and

Reliability Trials, initially working with John I. Thornycroft & Co.

Ltd. and subsequently in partnership with Geale Dickson.

'Scolopendra', 1903

Halliday was fortunate that his early career coincided with

a period of rapid development in marine motor engineering

and Thornycroft were at the forefront of this. In 1903 Mr Alfred Harmsworth, Lord

Northcliffe, offered the Harmsworth Trophy (re-named the British

International Trophy from 1904), the first annual international award for

motorboat racing.

Thornycroft’s entrant in the inaugural 1903 Harmsworth

Trophy race held at Queenstown, was ‘Scolopendra’, a 30ft. launch of

timber carvel construction, cedar planks on elm frames fitted with a

4 cylinder, 20 h. p. Thornycroft engine. The race was won by the

Linton Hope designed, 40 ft. launch ‘Napier I’ but it was concluded

that “considering her low horse-power, the Scolopendra was

undoubtedly the most efficient boat in the competition, easily making

15 knots.” (“A Short History of Motor Boating”, Bernard B. Redwood, 1906). ‘Scolopendra’

went on to win the subsequent “Yachtsman” Cup handicap race.

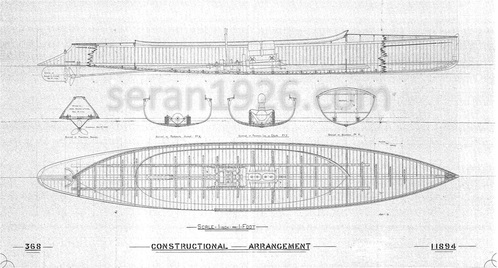

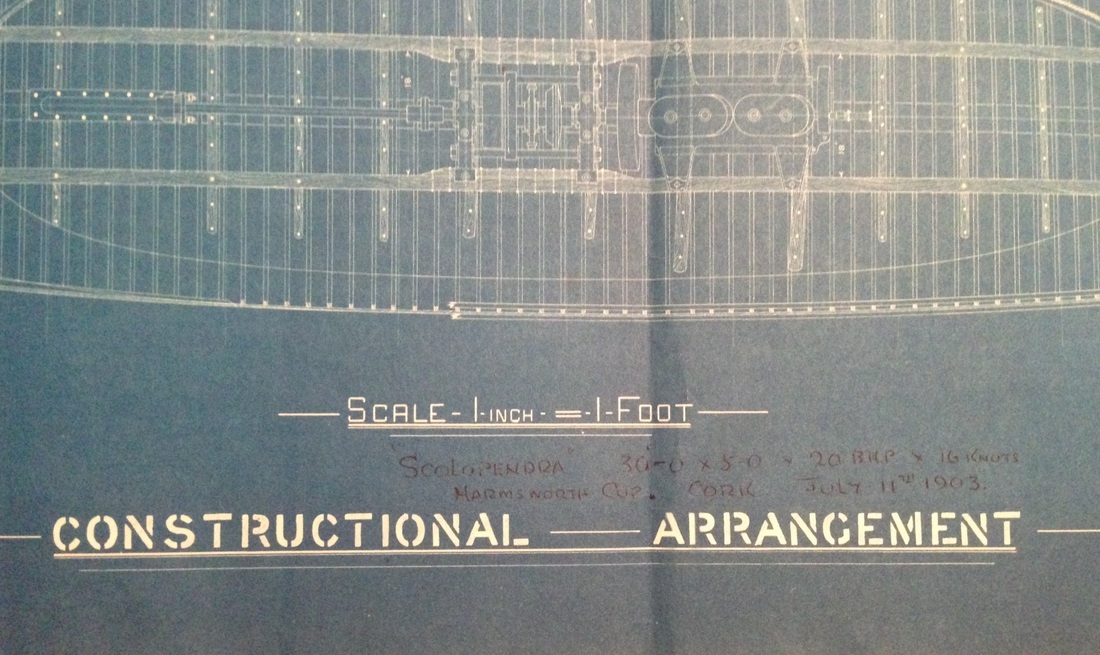

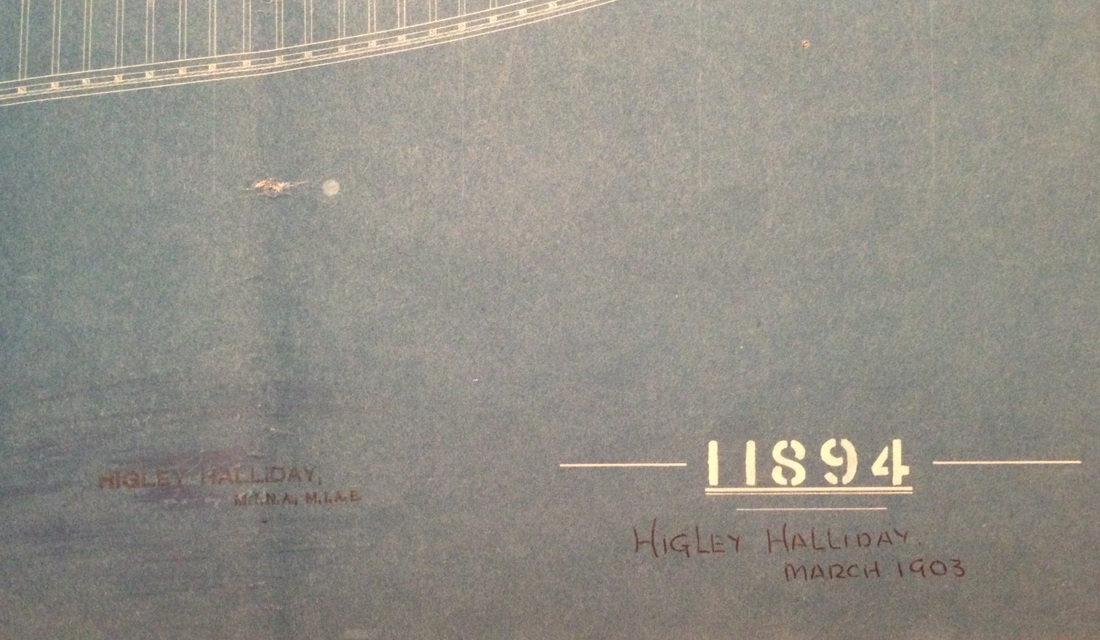

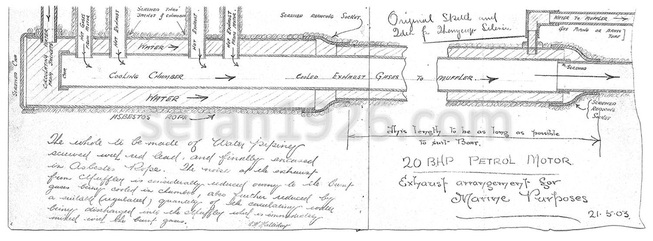

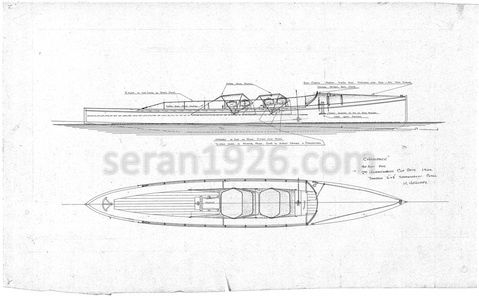

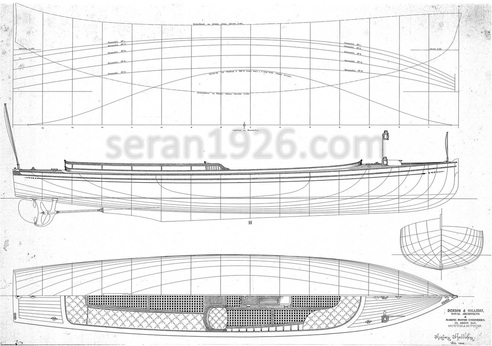

The extent of Halliday’s input into the design

of ‘Scolopendra’ is unclear, although a blueprint in his possession

showing Scolopendra’s ‘Constructional Arrangement’ and his sketch for a

marine exhaust for a 20 h. p engine, dated 21 May 1903, hint at a

close involvement especially in the context of his subsequent

work. Interestingly, the construction of the hull was subcontracted

to Frank Maynard’s yard and ‘Scolopendra’ may well have been

the first build which Halliday and Maynard collaborated on.

'Scolopendra II' and 'Champak', 1904

In early 1904, the Marine Motoring Association was

formed followed by the first annual reliability trials organised by

the Automobile Club through its Marine Motor Committee (in 1905

these were organised by the Motor Yacht Club and thereafter jointly

with the British Motor Boat Club). That year Halliday co-designed Thornycroft’s

motor launch ‘Scolopendra II’, entrant No. 26 in that year’s Reliability

Trials in Southampton Water and was at the helm with Tom Thornycroft

during the trials.

Halliday also designed ‘Champak’, Thornycroft’s launch

for the 1904 British International Trophy; an unusual design

featuring twin engines aligned in tandem. ‘Champak’ failed to arrive

at the start line in time for the start of the eliminating trials and

so did not make the shortlist of British entrants for the 1904 race,

but she did subsequently compete in the Reliability Trials.

In June 1904 Thornycroft’s Shipbuilding

Works at Church Wharf moved to Woolston near Southampton after

which the Chiswick yard was gradually closed down. Halliday also

moved to Southampton at this time and by early 1905, had entered into

partnership with Geale Dickson. Trading as “Dickson &

Halliday, Naval Architects & Marine Motor Engineers” located at

32 Above Bar, Southampton they specialised in the design of

motor launches such as the 20 ft. ‘White Heather’. Of interest (given

Halliday’s involvement with other Harmsworth Trophy entrants), was

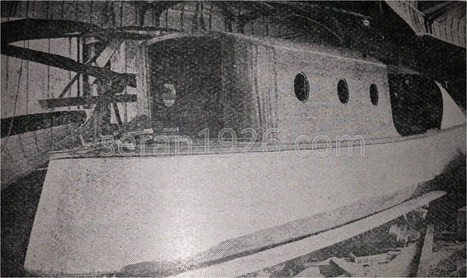

the acquisition by Dickson & Halliday of the hull of

‘Competitor’, (ex 'Napier Minor', ex 'Napier I'), designed by Linton Hope

and winner of the first Harmsworth Trophy in 1903. Acquired

from Commander Mansfield Cumming R.N. she was fitted with a

cabin and new Ailsa Craig engine and delivered to her owner on the Thames

in 1906.

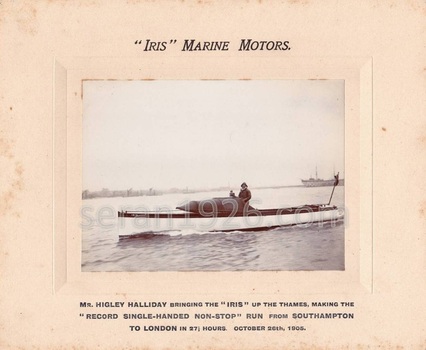

'Iris', 1905

In April 1905 Halliday designed and built the ‘Iris’

for Messrs Perman & Co. Ltd., sole agents for the Iris and

Kromhout motors. The ‘Iris’ was an open, 30 ft. motor launch fitted with

a 24 h. p. Iris petrol motor affording an average speed of 10

knots. Seemingly several motor engineers had reservations about the

reliability of the Iris motor and, Halliday, clearly keen to prove

otherwise, accepted a wager to run the 'Iris' single handed and non-stop

from Southampton to London Bridge. The ‘Iris’ departed from Southampton

at midday on Wednesday 25 October 1905 being met 20 miles

from London at Gravesend on the following day.

Smacking

somewhat of a promotional stunt orchestrated by Messrs Perman & Co.

Ltd. to promote the Iris engine and Halliday, his design, the voyage was

nonetheless a huge undertaking and a calculated risk that rewarded both

Perman and Halliday handsomely following the successful

run. The cruise was extensively reported in the national press

and undoubtedly helped establish Halliday’s reputation as an independent motor

boat designer. The editor of The Motor Boat summarised the achievement under

the heading “Halliday’s single handed run with Iris”.

“Complete success has, happily, attended the adventurous undertaking which Mr Halliday set himself when he wagered that the ‘Iris’ though only a 30 ft. open launch, albeit of a good sea worthy type, was a boat which he could successfully bring single-handed from Southampton round to London without a stop. Such a task is a trial of endurance which few would care to undertake, even under the best and most genial weather conditions. There is little pleasure in remaining alone in a small boat for at least 24 hours, and still less is there much enjoyment in attending not only to the navigation, but also to the engine during the same period, with the knowledge that a moment’s thoughtlessness might cause endless trouble. The very difficulties attendant upon the trip perhaps fascinated Mr Halliday : he knew the sea and its vagaries, the navigation of the Channel and the Thames estuary and he fully appreciated also the arduous character of the task, but he held a very favourable opinion about the Iris motor, and, finding himself at variance on that point with several motor engineers, was determined to prove that his confidence in the engine named was not misplaced. To do this, he undertook to set out on his trip without the means of restarting the engine should it for any reason stop ; he desired in fact, to leave the starting handle of the motor on shore. What would happen were the weather bad and the motor to refuse work did not enter Mr Halliday’s calculations. He was prepared to have to put back by stress of weather, but a breakdown of the motor – no, that was impossible he told himself.

All the arrangements for the run were made a little while ago, but it was not until Wednesday last that the run was made. There was not a crowd at Southampton to bid him good luck on his run. There were seven in all at the landing stage including Mr Dickson, well known as the partner with Mr Halliday in the firm Messrs Dickson and Halliday, and a representative of “The Motor Boat” charged with the duty of taking over the starting handle of the engine before Iris left for London and also of inspecting the boat to make sure that no handy instruments were on board to replace it. At 12 noon punctually Mr Halliday started off with the hearty wishes of the little group on the landing stage… As to the conclusion of the run, Messrs Perman & Co. – being the sole selling agents for the Iris motor were particularly interested in the run – took a party of press representatives down river on their useful boat the “Kromhout”. It was with the greatest pleasure and relief that we met Mr Halliday on the Iris about a mile above Gravesend. Ringing cheers greeted him from the “Kromhout” and scarcely had they died away when the motor stopped for want of petrol.

But Halliday’s task was really accomplished : it is true he was some 20 miles or so from London Bridge, but he had been through fog, frost, and at times a bit of sea, with all the accompanying hardships and dangers. It was a great feat and one which will long stand without an equal. That he continued the trip after his mishaps at sunset is proof of his moral courage. The run between the Thames and the Solent may in summer often be accomplished in an open boat with more than one on board, but, single handed at this time of year – no, it will not often be done. And if we admire Mr Halliday for his pluck, what will we say of the motor, and of the boat, which he himself had designed? It is such a triumph for British work and brains that our duty is not done until we have given credit where credit is due. The boat was built and designed by Messrs. Dickson and Halliday, of Southampton, and engined with an Iris motor British made throughout by Messrs Legros and Knowles at their London works at Willesden. Iris will be shown at Olympia by her owners Messrs Perman & Co.” (The Motor Boat, 2 November 1905)

Shortly after Halliday’s run in the 'Iris', the

engines’ manufacturers, Messrs Legros & Knowles held a dinner for the

press at The Hotel Cecil to exhibit their products for 1906. It was

clearly an enjoyable and successful evening with toasts to “The Firm” and

“Mr Halliday” interspersed with a “capital selection of songs.” At Olympia

that year both the ‘Iris’ and the ‘Kromhout’ were exhibited together with

a new reversible propeller designed by Halliday in 1904.

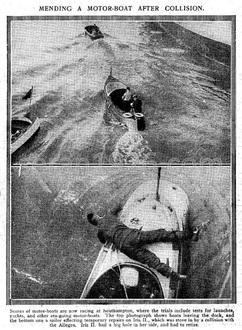

'Iris II' and 'Albatross', 1906

|

The motor boat reliability trials in Southampton Water

in 1906 afforded Dickson & Halliday the opportunity to

compete against the leading motor boat designers and marine engineers

of the day and build on the publicity and recognition that the ‘Iris’ had

afforded them. They entered a number of their designs including

the ‘Iris’, ‘Iris II’ and ‘Albatross’ in the trials with varying success.

In the 1906 eliminating race for the British International Cup,

‘Albatross’ took first and ‘Iris’ third place.

After suffering from a period of ill health,

Halliday’s partnership with Geale Dickson dissolved in

1906, with both designers going on to pursue individual careers.

Dickson remained near Southampton Water and continued to design

motor launches, including the motor yacht 'Wanderer' (1907),

‘Albatross II’ (1910) and ‘Albatross III’ (1912) amongst others,

continuing this work until the late 1920’s trading as Geale Dickson and

Co.

Halliday studied for the Yacht Master’s ticket by correspondence under Captain Duncan Forbes F.R.A.S. Nautical Academy, Southampton in late 1906 and in October 1907 he patented his design for “An improved silencer for internal combustion engines”.

|

'Thompson's Hydroplane', 1907 - 1909

In 1907 Halliday moved to Merseyside for two years to work

on the development of the 40 ft. “Thompson’s hydroplane” – notably larger than

other hydroplanes being developed at the time, which were typically less than

26 ft. Little is known of the project but hydroplane development was very much

in its infancy and Halliday was without a doubt at the cutting edge of this new

technology.

The British Admiralty had investigated the possibilities of

the hydroplane as early as 1876, although development was constrained by the technology

available at that time. One of the first hydroplanes was developed by the Comte

de Lambert in 1904 achieving a speed of 20 knots and was widely reported at the

time. The concept was developed further by M. Santos Dumont in 1907 who

undertook high profile trial runs on the Seine between Courbevoie and St. Denis

which were “a perfect success” (The Times, 25 September 1907) and by M. A.

Crocco & O. Ricaldini with their 26 ft. 3 ins. hydroplane design, reported

in the ‘Engineering’ Journal in October 1907.

The potential of the hydroplane to achieve speeds far in

excess of the traditional displacement hulls was graphically demonstrated at

the M.Y.C. Efficiency Trials in Southampton Water in July 1908, when brothers

Maurice & Claude Le Las and M. Bonnemaison unveiled their 13 ft. hydroplane

‘Ricochet II’.

“M. Le Las embarked and started his engine, being about to try a little impromptu race against Mr. Tom Thornycroft’s motor boat Gyrinus, which went well and is capable of some 18 knots ; and the hydroplane outpaced the motor boat with consummate ease. In fact it has shown itself capable of 40 km / hr, and a larger vessel of 20 h. p. is said to have done 55 km, while one of 30 h. p. has achieved 60 km.” (The Times, 5 August 1908)

The Times report of the Efficiency Trials at Netley

concluded that the ‘Ricochet II’ was a “very marvellous machine which, in all

probability, will be full of lessons to all students of movement by water” and

shortly after, that the hydroplane “had fired marine motorists generally with

an ambition to possess themselves these sporting little craft and to institute

races of hydroplanes. A good many orders have been placed, some of them in

England, for English hulls and English engines.” (The Times, 9 September 1908).

Halliday then, was at the centre of early hydroplane

development which was to transform the sport of motor boat racing and the

nature of the British International Trophy. Indeed, the experience gained on the

“Thompson’s hydroplane” project meant he

was ideally suited to working with Thornycroft’s and T. O. M. Sopwith in the

development of the Coastal Motor Boat in 1915.